Everything you wanted to know about Heraldry

Transcript of a talk given to C.U.H.&G.S.

Thursday, October 12th, 2006

This is very much an “introduction” to the subject of heraldry, aimed mainly at those who know little or nothing of the subject.

For those of you who know a lot about heraldry I can assure you that there will be nothing new in this talk. My advice to you is to either fall quietly asleep or drink the port, look at the pictures and think happy thoughts!

My talk this evening will cover the origins of heraldry, what it is and what it isn’t, the origins, purposes and development of personal heraldry in England and a brief introduction to blazon, the language of heraldry. I will draw attention to the significance heraldry can have for the genealogist.

HERALDRY! What a wonderful subject! And how blessed we are here in Cambridge with one of the richest resources anyone would wish to find. On Monday I walked from my office in Victoria Road to the Library in Petty Cury and back a round trip of about 30 minutes. In that time I counted 91 shields of Arms on the exteriors of buildings.

But what is Heraldry and why did it develop?

The origins of heraldry are much debated. In the Ancient world symbols were used to represent authority and to intimidate opponents in war. Many experts point to examples from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome as being the beginnings of heraldic design. The key element that distinguishes simple designs from true heraldry is that of inheritance.

That is not to say that there were not “heraldic” elements prior to the development of heraldry in Medieval Europe.

In the Old Testament, in the Book of Numbers (Ch 2 v 2-34), we find the following passage: “Every man of the children of Israel shall pitch his own standard, with the ensign of his father’s house … And the Children of Israel pitched by their standards and so they set forward, every one after their families, according to the house of their fathers.” This is the first clear mention we have of hereditary devices associated with individuals and their families.

Moving closer to our own time however Heraldry was a practical solution to a difficult and at times potentially fatal problem.

Come with me to the Battle of Hastings.

Those of you over 40 are no doubt aware that Saturday the 14th October is the 940th anniversary of the Battle. For those of you under 30 the Battle of Hastings was fought on the South Coast of England in 1066.

The invading Normans under their leader William the Bastard Duke of Normandy are arrayed at the foot of Senlac Hill. Positioned at the top behind their shield wall are the plucky Anglo-Saxons under their leader Harold, the rightful King of England.

The battle has raged for several hours the mounted Norman knights repeatedly charging up the Hill to attack the Saxons’ position but without success. At this crucial point in the battle the rumour sweeps the Norman army that their Leader, William, is dead. Panic begins to set in and the army is on the verge of disintegrating. To prove he is in fact alive William takes off his helmet and rides up and down his army’s lines showing his face to his troops.

If you know the Bayeaux Tapestry you’ll remember the scene with one of William’s knights riding along behind pointing at William and saying “look, it really is him”. Except in Norman-French. The calm is restored, the battle continues and the rest is history. And so begin a thousand years of Norman oppression … Discuss.

Needless to say, taking off your helmet in the middle of a medieval battle was not the most sensible thing to do. It could be fatal. One hundred years after Hastings Geoffrey de Mandeville, 1st Earl of Essex, is riding fully armoured with his not so merry men through the fens, near Ely, when he is ambushed. With his vision impaired by his helmet he decides to take if off and look around. He gets an arrow in the face as a result and falls dead from his horse.

Add to this the sheer practical problems for a knight on horseback. With a shield on his left arm, the reins held in his left hand and a sword or lance held in his right the chances of removing a helmet or raising a visor were remote to say the least.

What knights needed was a simple clear means of identification. Something that would be unique to them. After all you don’t want turn up to a battle or a tournament and find someone else with your device. It needs to be large enough and clear enough to be seen even in the fog of war, but not so cumbersome as to impede the knight going about his job (killing people and avoiding getting killed). It should be said that there is another school of thought which discounts this idea and make the point that in the mud and debris of war any designs would soon be rendered unrecognisable. They prefer to see heraldry develop from the need of a small feudal elite to possess some exclusive means of identifying themselves. Your choice of arms not only set you apart from the common herd it also enabled you to display your family or feudal affiliations, many early coats of arms link the different branches of the same family together. Vassals adopt similar arms to their lords. The same devices are used but the colours are changed.

Men also had the need for personal seals to sign documents and witness charters. A coat of arms is ideal for this being as personal to you as a signature. You could also use your arms, or a badge to mark your property and even identify your servants and your soldiers.

In the early medieval period shields changed from the long kite shaped shield of the Normans into shorter and squarer shields, and it is to these that the marks and devices were applied for the purposes of identifying one knight from another.

If we recall the Bayeaux Tapestry you will notice that many of the shields have designs. This is not strictly speaking heraldry, because it lacks one key element. That is, there is no evidence these designs were hereditary.

True heraldry is heritable. When a knight died he passed on to his son his castle and lands and his sword and shield, and with his shield went his coat of arms as well. The earliest example of this comes with the Plantagenets. Geoffrey of Anjou was given a blue shield spread with golden lions by his father-in-law Henry I in 1127. His son Henry II in turn passed the same arms to his eldest, albeit illegitimate, son William Longespee Earl of Salisbury.

As a rule the oldest heraldry is the simplest. It had to be simple and it had to be striking. You had to be able to identify at a distance and in a hurry whether the man charging at you with warlike intent was on your side or on the other side. A squire would learn the rules of heraldry and more importantly he would learn to identify the arms of the knightly families both in his own country and those abroad.

Getting this identification wrong could lead to disaster on the battlefield. The Yorkist badge was the famous Sun of York and consisted of the white rose of York set within a sunburst. All of Edward of York’s troops would have worn this on their clothes. At the Battle of Barnet in 1471 the Yorkists did battle with the Lancastrians. Amongst whom was Edward de Vere Earl of Oxford.

The de Vere badge was the Mullet, a silver five pointed star, again all his servants and soldiers would have worn this. In the mist and confusion of the street battle the de Vere star was mistaken for the Yorkist sunburst and De Vere was fired on by his allies. Up went the cry of treason De Vere left the field in a fury the Lancastrians were defeated and Warwick the Kingmaker slain.

After a number of years of individuals adopting their own Coats of Arms some confusion inevitably set in. Heraldry had to be codified. Each kingdom had its own heralds whose job it was to record and grant coats of arms and to settle disputes. The heralds in England are still members of the Royal Household and still receive the same salary they did in medieval times, £13 10s. King Richard II gave them a pay rise and they haven’t had one since. Many great lords had their own heralds, though these have died out.

Heralds were given the job of resolving disputes about who was entitled to bear which Coat of Arms, and were given their own court of law, the Court of Chivalry to do it with. The classic example of an heraldic dispute is that of Scrope and Grosvenor.

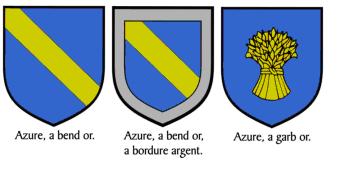

In 1385 King Richard II of England invaded Scotland with his army. During the invasion two of the king’s knights realised that they were using the same coat of arms. Sir Richard Scrope from Bolton in Yorkshire and Sir Robert Grosvenor from Cheshire. Both were bearing arms blazoned Azure a bend Or. When Scrope brought an action Grosvenor maintained that his ancestor had come to England with William the Conqueror and that he had borne those arms and his descendants had used them thereafter.

The case was brought before a military court presided over by the High Constable of England. Several hundred witnesses were heard, amongst whom were John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and Geoffrey Chaucer. It was not until 1389 that the court decided in Scrope’s favour. Grosvenor was allowed to continue bearing the arms with a bordure Argent for difference. Neither party was happy with the decision, when King Richard II gave his personal verdict on 27th May 1390 he confirmed that Grosvenor could not bear the differenced arms. His opinion was that these two shields were too similar for unrelated families in the same country to bear.

Grosvenor had to choose a new shield, though. He assumed arms of Azure a garb Or and these arms are still used by the family’s descendant, the Duke of Westminster.

They say that revenge is a dish best served cold. The Grosvenors, who by the late 19th Century had become the fabulously wealthy Dukes of Westminster had very long memories. The 1st Duke had a promising racehorse which he named Bend Or in honour of the family’s lost coat of arms. In 1880 nearly 500 years after the judgement went against them Bend Or won the Derby.

For the design of coats of arms Heralds came up with some simple rules. The heraldic palette was divided into Metals (gold and silver) and colours (red, blue and black) green was added in the later middle ages, it has always been a difficult colour to make and was very rare. In addition there are the furs. The two basic furs are Ermine and Vair. The variations come about by altering the combinations of colours used. Vair is supposed to be the alternation of the back and belly fur of the grey squirrel, Cinderella’s slippers are thought to have been made of Vair, until a bad translator got confused and wrote down Verre the French for glass. Squirrel fur would have been a good deal more comfortable.

Heraldry also has its own language called Blazon. Most of the words have their origin in Norman French and so Gold is Or, Silver is Argent. Blue is Azure, Black is Sable, Red is Gules and Green is Vert. For use in black and white these can be represented by lines or dots.

The basic rule was never put a metal on a metal or a colour on a colour. A black lion on a blue shield is very difficult to make out. If you look at modern road signs the same principles apply, and for the same reasons. A 30 mph limit sign is a white disc (in heraldry argent or silver), edged in red (gules) with black (or sable) numbers on it. Whenever I see a sign for “no speed limit” I automatically thing “Argent a bend sinister sable”, when that happens you know you’ve probably become obsessed by Heraldry. But you can see that the same palette has been utilised to make bold and clear designs.

Heraldry soon became a mark of the knightly class. A knight would cover not only his shield with his coat of arms but also his surcoat. He would top his helmet off with a crest (at least for tournaments as they were rather impractical in war). The cloth covering his horse would also be woven or painted with his arms. Even his followers would wear his livery colours (often taken from his arms) along with a badge. Badges became very common, they often survive in pub signs, the Bear and Ragged Staff of the Earls of Warwick, The White Hart of Richard II, the Rising Sun of the House of York, Blue Lions and Red lions, and so forth.

Here we see a representation of the Battle of Crecy by Dan Escott.

As you can see it is rather stylised but it shows very clearly the use of Heraldry for identification for a large number of men. Each knight shows his arms on his shield and on his banner and each has a crest on his helmet. So one can spot Courtenay, FitzAlan, Cobham, Latimer, Neville, even the Bishop of Durham. Here are the arms Azure a bend or. As Crecy was fought in 1346 we can’t be sure whether we are looking at a Scrope or a Grosvenor, my money would be on Scrope.

So what is a coat of arms?

A coat of arms, also called an achievement of arms, has two basic elements.

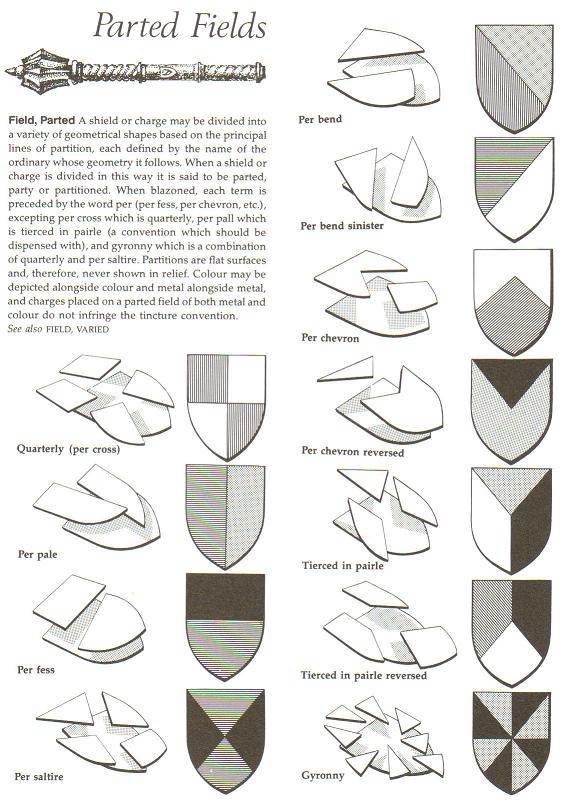

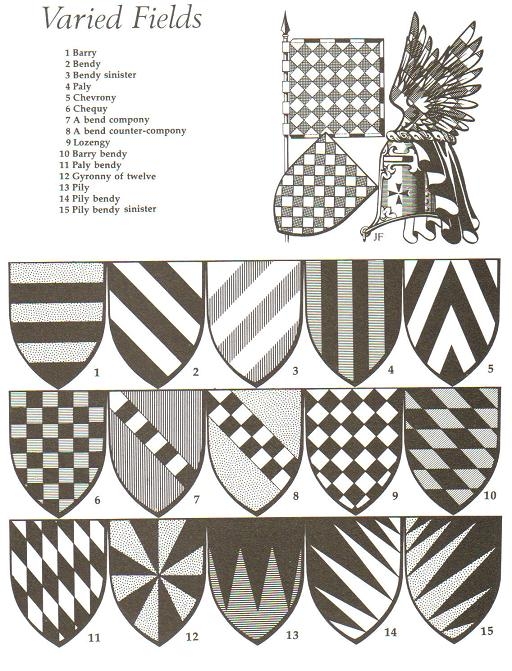

The first is the shield. The shield in turn bears charges, or is divided up by lines to form patterns, often a shield will have both elements together. But whatever elements are used to make the design they must always follow the basic rules of heraldry about not putting a colour on a colour or a metal on a metal.

As you would imagine the oldest coats of arms are the simplest in design. It was only when more men became entitled, or aspired to, coats of arms did the need arise to make them more complicated. This can often be a useful dating tool for a coat of arms. Heraldry has fashions just like clothes. A shield can “look” 15th Century, another maybe unmistakably late 18th Century.

Another useful dating tool can be the shape of a shield. The shield of the 12th and 13th Centuries forms the classic “heater” shape shield. It looks like the bottom of an iron. Items placed on the shield were designed to fit the space available. By Tudor times shields were no longer used in war. The shield shape became squarer, almost rectangular. This in turn led to charges being used to fill up this shape. Sometimes a shield will look crowded, the charges may look squashed or elongated. This can be because a design made to fit comfortably into a Tudor shape shield are being displayed on a much earlier shape for which they were not designed. A bit like trying to fit a model of Rubens into a mini-skirt.

The easiest way to divide up a shield is to use lines of partition and ordinaries. Cutting the shield vertically and colouring one side red the other silver, will, for example give you the arms of the Waldegrave family. A thick stripe across the centre of the shield is called a Fess. A diagonal stripe is called a Bend and so forth.

The next way to make a design is by using Charges. Anything under the sun, and indeed the Sun itself can be a charge. Lions and eagles are the most popular but the whole animal kingdom has been raided at one time or another for Charges.

Heraldry has a very large bestiary to call upon. Practically every living creature has its place in heraldry from bees and grasshoppers to elephants and whales. In addition there are mythical beasts such as the Yale (which was supposed to be able to swivel its horns in any direction - splendid Yales can be seen over the gates of St John’s College Cambridge) and the Griffin. Traditionally Griffins were supposed to guard treasure. As such they are thought appropriate symbols for banks. When they have wings they are said to be female. Unfortunately no-one told the Midland bank this because they used Richard Briars to do the voice-over for a creature that every student of heraldry knew to be female.

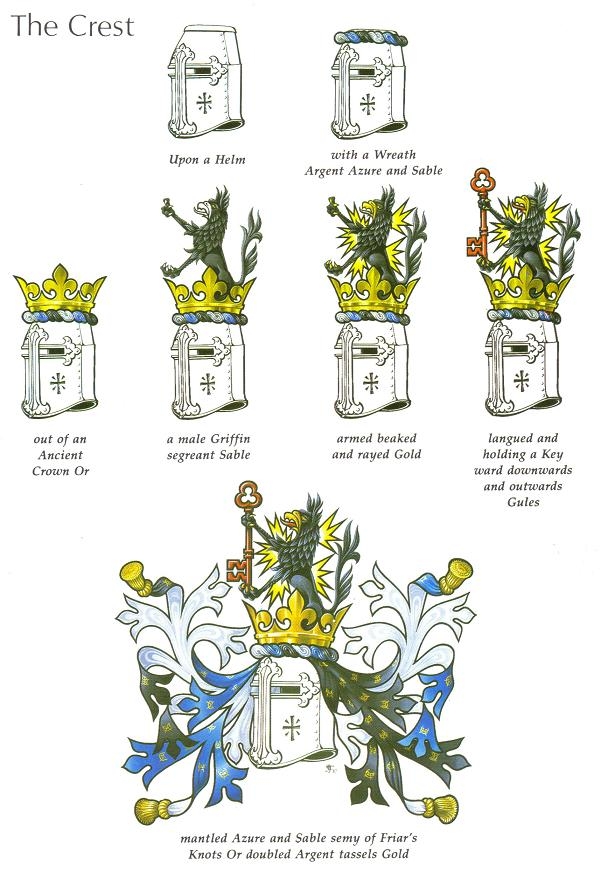

Inanimate objects can also feature anything from a locomotive to an atomic particle. The second element of a coat of arms is the Crest. People often talk about “The Family Crest” when they in fact mean the coat of arms. The Crest is technically the device made to sit on top of a helmet. Crests were originally made from light materials and were unlikely for practical reasons to have been worn in battle. They really came into their own in Tournaments. Crests often, but by no means always, repeated charges or other elements from the shield. But they could be completely different. The earliest crests may well have been painted onto a metal fan that sat on top of the helmet.

Rank can be judged by the helmet used. The sovereign’s is gold and faces the front. A peer’s is silver with gold bars and faces the side a baronet’s and knight’s is steel has an open visor and faces the front and a gentleman’s is a steel tilting helm facing to the side.

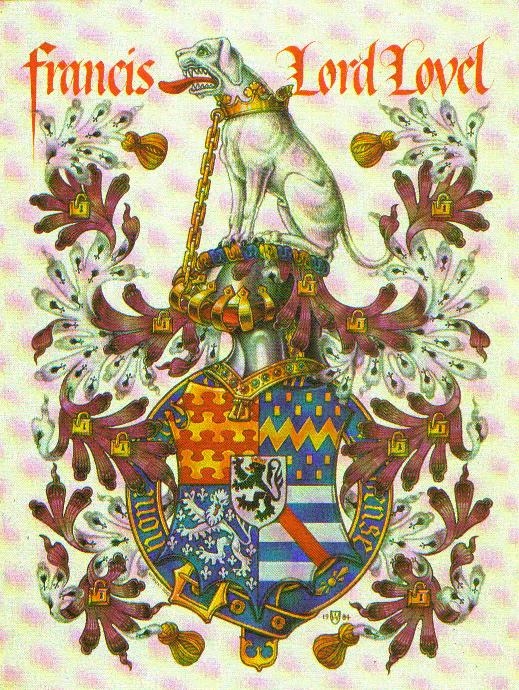

Here we see the arms of Lord Lovel, one of Richard III’s henchmen.

In the centre we see his quartered coat of Arms, surrounded by the Garter and above his helmet his Crest. The helmet is surrounded by Mantling. Mantling is supposed to represent a cloth hanging from the back of the helmet cut and slashed by swords. It has its origins, so it is said, in the cloths used by Crusaders to shield their helmets from the sun. The quarterings show the various ways of designing a shield. In the First Quarter we have the paternal Arms of Lovel, using a division of the shield using a pattern called Nebuly. In the second Quarter the Arms of Deincourt show two types of Ordinary, a Fess in this case Dancetty, and billets. In the third Quarter the Arms of Holland show the Charge in the form of a lion rampant. The fourth quarter for Grey of Rotherfield has a division barry and an ordinary in the form of a bend. The inescutcheon is for Burnell.

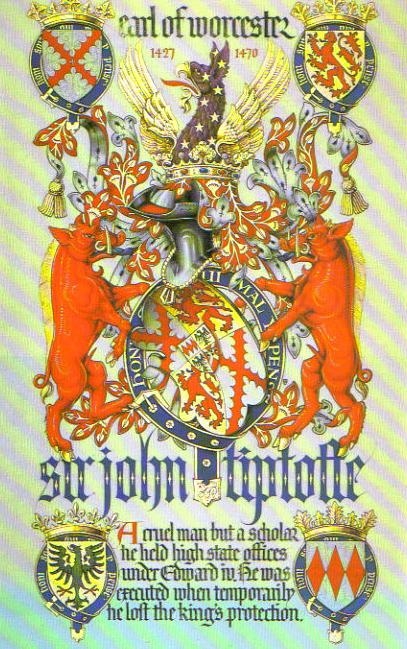

Here we see another achievement of Arms. The Arms of Sir John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester. Also quartered, again with a Crest and Mantling. He is a Knight of the Garter. He also has Supporters. Supporters are there to hold up the shield from either side. Only peers of the realm and Knights of the Orders of Chivalry are entitled to Supporters as a rule. Sometimes they are chosen from Charges in the coats of arms, others have no connection with it at all. They are either human or birds and animals. The only rule is that they must be the same size. So a mouse on one side would be shown the same size as an elephant on the other.

As I mentioned both these shields have quarterings. Quarterings can be very useful to the genealogist when deciphering a family’s ancestry.

Quarterings only really appear in the late medieval and Tudor period. Before that date coats of arms were limited to the knightly class, they all knew each other and had no need to compete in showing off their illustrious pedigrees. Also a quartered shield defeated the prime objective of a shield in battle in that it hindered its simplicity and clarity.

However, things changed when almost anyone, as long as he had money, could BUY a coat of arms and start showing off to all and sundry his newly acquired “gentle” status. Understandably this upset those who had inherited an old coat of arms. To a certain extent the fact that they bore a simple coat of arms marked them out from the crowd, very often first grants were packed full of allusions and different charges making them quite crowded, but later generations soon caught on and asked for simpler more “ancient” looking arms.

A classic example is that of the Spencer family. The first Spencer who was granted a coat of arms had done very well for himself in the wool trade and owned lots of land in Northamptonshire. When the time came to become a gentleman he went to the College of Arms and bought a typical nouveau riche coat of arms and not at all attractive. His son who was moving in court circles and competing with the best in the land didn’t like it at all. So he went back to the College of Arms paid even more money and the heralds “discovered” much to Mr Spencer’s delight that he was in fact descended from the great medieval family of DeSpencer. On the basis of this spurious genealogy he had another coat of arms granted to the family, this time copied directly from his “new” illustrious ancestors, it was much simpler, more striking and not nouveau at all. The family liked it so much they use it to this day.

A similar story can be told about the Montagus of Boughton and of Hinchingbrooke House and Sir Thomas Audley (who refounded Magdalene College here in Cambridge and whose Arms the College bears to this day). He included an allusion to the great medieval house of Audley even though he himself could prove no connection with them. He also added eagles to his coat of arms, a very Royal and noble attribute. Not bad for a poor grammar schoolboy from Essex. However I suspect the Heralds had some fun and Thomas’s expense. His Coat of Arms also include two martlets. Martlets were heraldic swallows. In the Middle Ages swallows were thought never to set foot on the ground, and so had no feet just tufts of feathers. As such they were thought appropriate for men who had no “base”. Men who had risen from nothing.

Confronted by people like the Spencers and the Montagus what could the old nobility do? One thing they had that the upstarts didn’t was ancestors who had married heiresses, to be more precise Heraldic heiresses. A daughter of a man entitled to bear arms but who had no brothers to carry on the family name, and so pass on the family arms, could pass on her father’s arms to her sons by way of quarterings. Always assuming she had married a man also entitled to bear arms. She could also pass on any quarterings inherited by her family.

Families such as the Percys and the Howards (who were pretty arriviste themselves) in the past had been proud to display their simple paternal arms. Now, faced with men like Thomas Audley, Cardinal Wolsey and a host of Russells and Spencers they delved into their family history (or paid a herald or genealogist to do it for them) and began to display the more illustrious connections in their coats of arms safe in the knowledge that these “new” men could not compete. If you could flaunt a Royal connection, preferably Edward I or Edward III so much the better.

One thing to bear in mind is that though they are called Quarterings they need not be limited to four. You can in fact have any number they are still called quarterings. The one rule you should follow is that you cannot cherry pick which arms you want to display. If you are descended from a famous family but only through one or more rather more obscure heiresses then those connecting arms must be shown too. You must also display them in chronological order. The oldest first.

If your family is old enough and your ancestors made a habit of marrying heiresses then the number of quarterings you could accumulate could be staggering.

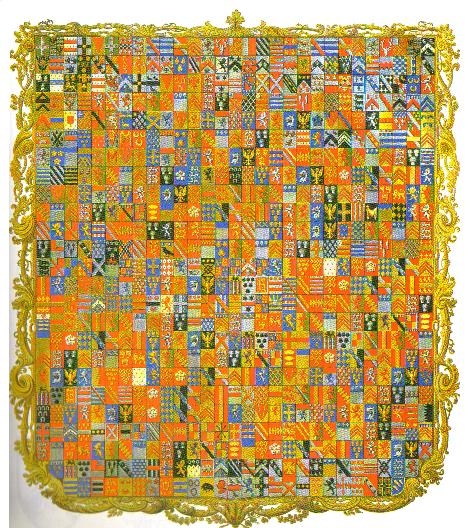

The Grenville family of Buckinghamshire eventually acquired a five-barrelled surname (Temple-Nugent-Bridges-Chandos-Grenville) a double-barrelled Dukedom (Buckingham and Chandos), many houses and 719 quarterings.

The paternal arms of Grenville are in the first quarter thereafter it is possible to trace the families connections using the heraldry of the heiress families they married into, though not of course those wives who were not heiresses.

The family had a direct Royal lineage and so the Royal Arms of Henry VIII feature here along with such families as Waldegrave (which I mentioned earlier), Neville, Grey and Clare.

The family went spectacularly bankrupt not once but twice and died out in the male line at the end of the 19th Century. Their principal seat, Stowe, is now a public school.

If you want to see the entire history of one family shown in heraldry you can do no better than go to Audley End and look at the ceiling of the family pew in the Chapel. There the descent of every generation of the Griffin family is shown.

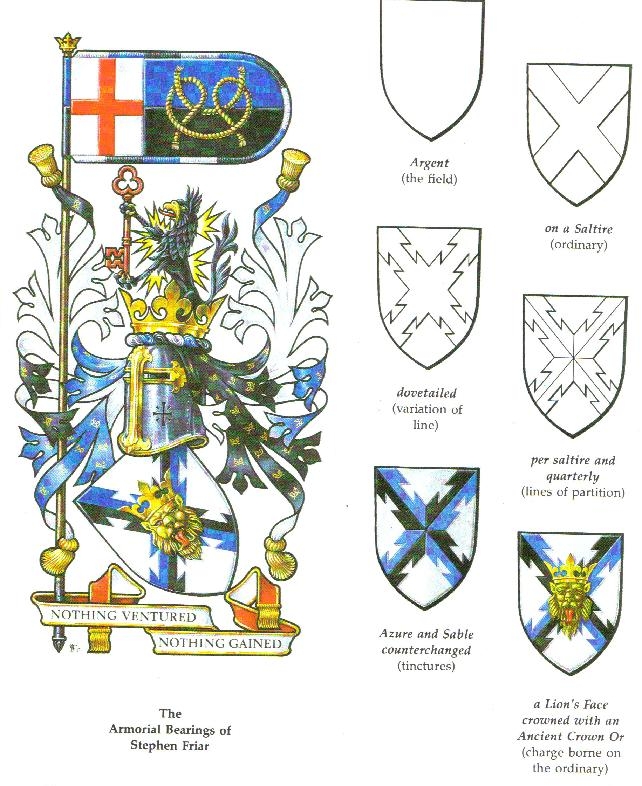

I would now like to turn to Blazon. The Heraldic language used to describe a Coat of Arms and its constituent parts in such a ways as to record accurately the design so that it can be reproduced using nothing but the description.

The basic rule is work from the back to the front. Heraldry has its own terms that stem in the main from Norman-French and act as a sort of shorthand to describe shapes and attitudes of charges.

We begin with the base colour of the shield in this case Silver or Argent usually shown as white. Then the principal Charge in this case a diagonal cross or Saltire. You then describe the attributes of the charges, in this case it is Dove-tailed and also sub-divided Per saltire and quarterly. The colours of the charge are then described Blue (or Azure) and Black (or Sable) counterchanged i.e. swapped around. Finally the last charge is a Lions face crowned Or (which means gold). Once the terms are leant anyone can produce this coat of arms from the description.

The same principles apply to the Crest.

Finally: How do I get a coat of arms. By far the easiest way is to inherit one. If you can prove an ancestor in the legitimate direct male line was granted a coat of arms then you can use those arms. However unless you are the eldest son of an eldest son its not quite as simple as that. Only the eldest son may inherit his fathers “undifferenced” coat. All other sons and their descendants should, in theory at least, add distinguishing marks to the shield to make them different to the arms in the main line. This can get rather complicated and would if taken to its logical conclusion be rather cluttered so other methods are sometimes employed.

If you are not descended from an Armigerous ancestor, or if like the Spencers do don’t much like the arms your ancestor chose, then you can go to the College of Arms petition the Earl Marshal who acts on behalf of the Queen in matters heraldic so that you might be deemed worthy of a grant of arms. Membership of a professional body or a university degree is usually sufficient, and criminal conviction probably enough to get it declined. Then together with a Herald of your choice you can design your own coat of arms. One word of warning. Heralds, from time immemorial have been and still are addicted to puns. In heraldry this is called Canting. This can in fact be a boon for the herald or genealogist confronted with an unknown coat of arms. Look for a pun and you often won’t be far wrong. You just have to understand the way heralds minds work. For example if your name is Harris the chances are you’ll get a hedgehog on your coat of arms. The reason; the old English for hedgehog is Herries, which to a heralds ear is close enough to Harris to warrant its inclusion. The arms of the Cornwallis family of Brome Hall in Suffolk include Cornwall choughs, another example of canting heraldry. The Arundell family of Wardour Castle in Wiltshire have six silver martlets on a black field. Martlets as we saw in the arms of Audley are swallows. The French for swallow is Hirondelle, which is near enough to Arundell to warrant their use as a charge.

The motto is also a good place to look for a clue to a family’s name. The motto is in fact not technically part of a grant of arms. In theory every generation can choose a new one. In practice they don’t and so the motto too becomes inherited.

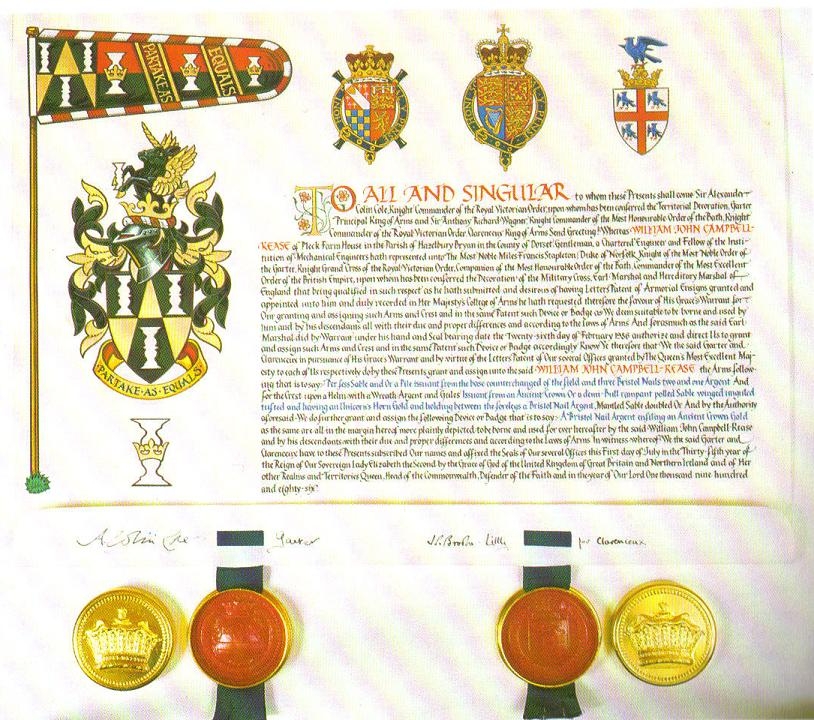

Once agreed by the head of the College of Arms, Garter King of Arms, you get a very nice illuminated manuscript to take home and a coat of arms you can pass on to your children. The Heralds, as I said earlier though members of the Court haven’t had a pay rise since the reign of Richard III so they will expect hard cash in return for their expertise.

(A personal grant of arms in England.)

I have talked about personal heraldry in England. Scotland has its own rules and traditions, and the nations of Europe and beyond, such as Japan, have their own distinctive coats of arms and rich heraldic traditions. Some countries as diverse as Russia and Haiti invented entire heraldic styles and traditions in a matter of a few years, as did the France of Napoleon.

I have also been talking about Personal Heraldry as it relates to England, there are still the areas of Corporate Heraldry, Municipal and Civic Heraldry, National and Ecclesiastical heraldry which are subjects in themselves. I haven’t touched on Hatchments or Augmentations of honour - see the Arms of Churchill College for one of those. All of these, any many others can be explored here at C.U.H.&G.S.

Finally the great thing about heraldry is not only is it pleasant to look at (at least it should be though this is not always the case), not only is it linked directly to a family and so very personal, not only can it be of use to the genealogist, but we are most fortunate in this country that it’s practically everywhere. If you go to a Church you will find it, if you look on the façade of the Town Hall and Shire Hall you will find it, and of course here in Cambridge we are blessed with one of the richest resources of Heraldry anyone could wish for in the Colleges. I have mentioned the Yales at St John’s and at Christ’s, go and have a look at the porcupine at Sidney Sussex, you even have the arms of Jesus (and I don’t mean the College) clearly visible on the façade of Sidney Sussex, see the Royal Heraldry of Edward III over the Great Gate to Trinity College. One day I think I will arrange an Heraldic treasure hunt around Cambridge, its amazing what you can find if you just look up.

The best thing about Heraldry like any good subject you can never learn all there is to know about it.

Thank you.

Acknowledgments: Most of the pictures for this talk have been taken from A New Dictionary of Heraldry by Stephen Friar whose indulgence I crave.