Peter Murray Jones – Fellow & Librarian, King’s College, Cambridge

Dr Jones addressed the Society in the Thirkill Room at Clare College on Thursday, 22nd April, 2004. This article is based on his remarks on that occasion.

From the beginning its founder Henry VI seems to have intended to erect in the College of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Nicholas a peculiar jurisdiction, independent of Cambridge University. To this end he procured no less than nine papal bulls from Pope Eugenius IV, dated 29 November 1445, exempting the College from the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop and Archdeacon of Ely, the Chancellor of the University and all other judges ordinary, and placing it under the sole jurisdiction of the Bishop of Lincoln. Jurisdiction included cognizance of personal actions, corrections, and probate, and defined the precinct of the College as all the soil of the College enclosed within stone walls on the south, north, and west, and on the east still to be enclosed, ‘as it lies on the west side of water called ‘Le ee’’. No other college in Oxford or Cambridge claimed such a jurisdiction.

The first recorded exercise of probate jurisdiction by the Provost took place on 22 February 1451/2, when the 1449 will of a William Roskyn was proved. At first business was slow, only fourteen wills in the fifteenth century. In the next century things picked up, though there were never more than eight wills proved per decade. For the seventeenth century the average per decade rose to twelve, and even the Civil Wars did not affect the figures drastically. After the 1720s though there is a distinct tailing off in the number of wills proved, and the very last will is that of Edmund Holt Esquire, late Senior Fellow of King’s, proved in 1794. Why did people want to make use of the College jurisdiction in the first place ? Convenience for those living in the precincts was no doubt part of it, as perhaps was cost, though we do not know what the Provost charged for his services. Many of those whose wills were proved in King’s wanted to remember individuals connected with the College, or the College itself, in their bequests, or to take advantage of Chapel burial and post-mortem masses and prayers, before the Reformation swept all that away.

There are in all 221 wills and letters of administration in the Ledger Books at King’s, spread over nearly 350 years of probate jurisdiction. The original wills do not survive, only the copies made as a record of probate. Probate jurisdiction applied to College tenants as well as members, plus perhaps some servants who worked rather than lived there. Not everybody at King’s chose to have their wills proved there, for between 1504 and 1729 there are 62 wills and administrations for King’s people registered at the Vice-Chancellor’s Court.

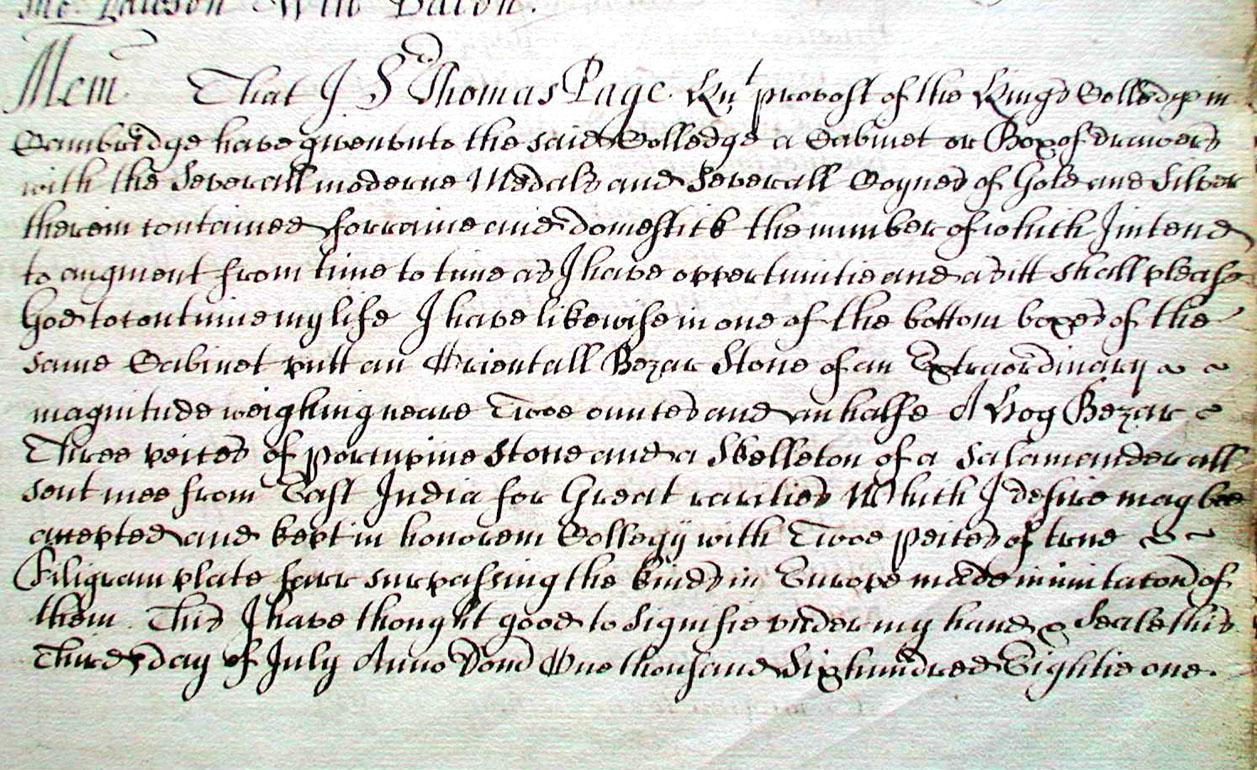

The most important people whose wills were proved in King’s were six Provosts; they lived very well by Cambridge standards in palatial housing on King’s Parade. The first is John Argentein, doctor to royalty and alchemist. He described himself in his will, dated 25 January 1507/8, as ‘unworthy priest and penitent sinner’. The main purpose of the will seems to have been to specify the brass memorial still to be seen in the Chapel. He wanted to be shown in front of a crucifix praying, with the verses, ‘crucified redeemer of humanity , son of the virgin and of God, remember me’ and with a legend stating that ‘here lies the body of John Argentein, student of art, medicine and of scripture, let whoever passes by say a prayer that Argentein may live in Christ’. Most spectacular of all Provosts’ wills was that of Sir Thomas Page, made 3 November 1680. He left lands in Harrow to relatives, and many valuable cups and jewels to Fellows. The most intriguing item was in a codicil, leaving the College a cabinet of curiosities with a huge bezoar stone, three pieces of porcupine stone, and the skeleton of a salamander, all from the East Indies. Alas there is no trace now in King’s of Sir Thomas Page’s cabinet.

Codicil to will of Sir Thomas Page, Provost, 1681 (Ledger Book 7, fol. 6)

Before the Reformation, there was often quite a lot of liturgical detail, as with Vice Provost John Sampson, whose will of 3 August 1517 requested masses to be said in the ‘new church’ at the altar of ‘scala celi’ (we do not know exactly where that was in the Chapel), and made bequests to a fellow, conduct, scholar, and chorister. After the Reformation there were no more masses, but there were still requests for particular priests or fellows to give a funeral sermon. Wills were uniformly written in Latin before 1517, when we find the first example of a will written in English for Steven Woode.

Bequests of clothing and of beds are the most common sorts of mobile property represented in the King’s wills; gowns of various colours and feather beds go to relatives or sometimes to fellow scholars, but books and musical instruments also turn up quite often. The will of John Node ‘clerke of the kingis college ...seke of body and hoole of mynd’ in 1519, is one of the most elaborate examples. He left service books to Trumpington, Grantchester, and St Botulph’s churches, medical books to Dr John Grey, and ‘all my tools a stillatory a serpentyne a gryndying stone with a mortar and all my bookis save those that be bequethed’ to Mr Dussing, astronomer and alchemist. The College was left all his pricksong books, and John Glasier his clavichord boards with their plan, and a painting frame.

Sometimes we get glimpses of the academic business of the College. In the year 1560 George Smythe, B.A., left books to his colleagues that included his own notebooks of divinity and philosophy. He must have thought these compilations would be useful for their studies. Most often though we see in these bequests the desire to be remembered by friends. The wills recorded in the Ledger Books can give us invaluable insights into the ways of life and death in the college, as well as glimpses of the townspeople and college servants who had close ties to the college.

Return to:

Contact Officers of the Society by electronic mail.

Cambridge University Heraldic and Genealogical Society